Final Report

Video

Project Summary

In Minecraft, ghasts are large flying mobs that can shoot fireballs at the player. The player can deflect the fireball by hitting it with the correct timing. Here is a video on how it works:

For our project, our agent will learn how to kill ghasts by deflecting fireballs back at them. Our agent will be given the position of the ghasts in the environment and the position & motion of the incoming fireballs. The agent will then learn where to aim and when to swing its punch to redirect the fireball to the ghast.

This may initially appear to be a relatively simple problem to code a solution for manually - in fact, we did. However, it was dramatically outperformed by our final AI agent. An AI we created entirely from scratch without the use of any external libraries except numpy and quaternionic, outperformed the handmade solution 4x in simulation. We will attempt to explain our approach, including our pitfalls and shortcomings as well as our successes, here.

Approaches

Initially, we took 2 approaches towards training the AI: a neural network and RLLib’s Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm. We later chose the neural network to be our main training approach because it provided better results and shorter training time as opposed to the reinforcement learning approach.

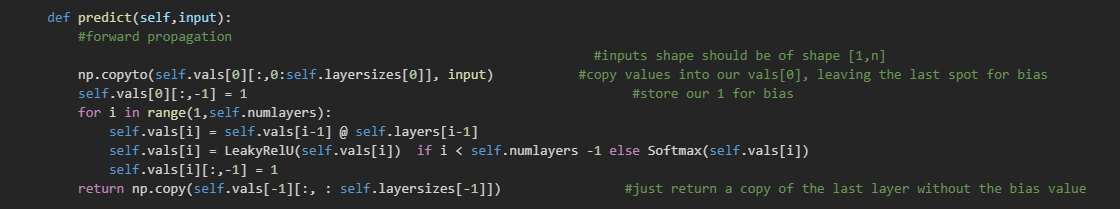

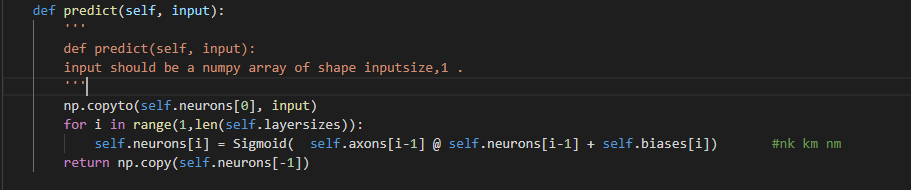

The neural network started out as a Jupyter Notebook version based off of a Youtube tutorial demonstrating digit classification - Neural Network Explained. It took a few days to get a version that can predict values, and a few more to get back-propagation working. In the beginning, we tried using different activation functions, but none of them worked well with NaN values except for the sigmoid function. So, we continued using the sigmoid function for the next version. The best accuracy that the early version achieved was 90% with 1 layer.

For debugging purposes, the neural network was moved into an actual .py file so we can use breakpoints. The neural network was redefined to be more general and has a variable shape, making it version 2. Once that was working, one of our team members tried learning PyTorch with the eventual goal of doing evolutionary learning. He quickly discovered that PyTorch was very geared towards gradient descent and copying a network using PyTorch could be huge hassle. In the end, he decided not to use PyTorch and adjusted our already-working network for evolutionary learning, titling it version 3.

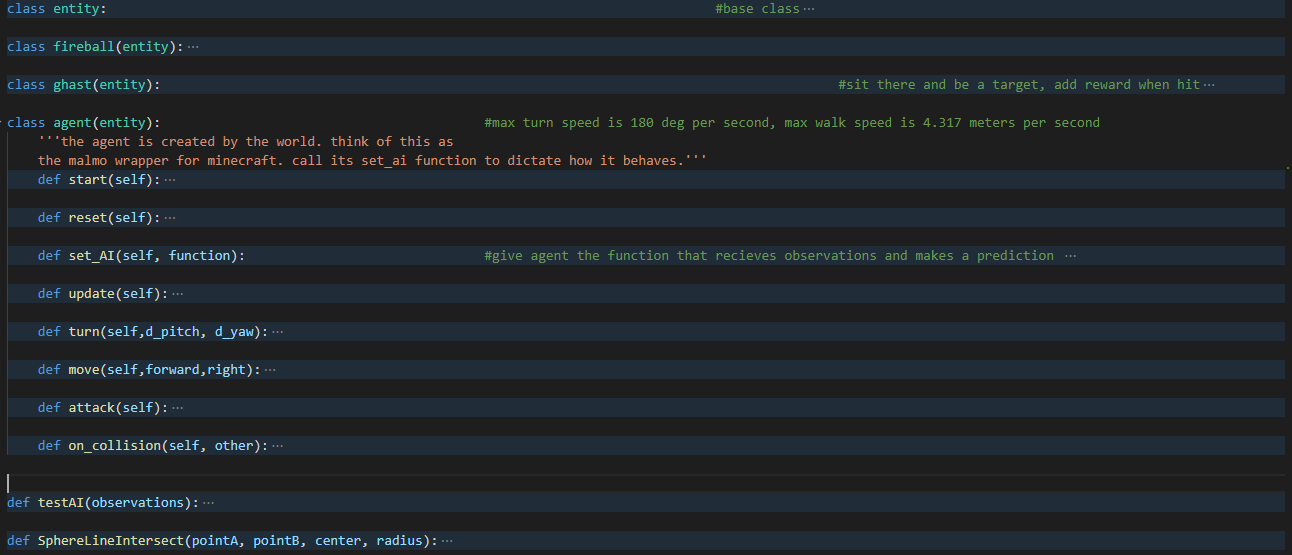

After the learner was done, we needed a way to accelerate the training process. The notminecraft.py script was created with the goal of (from the agent’s perspective) perfectly emulating the observations it would get from real Minecraft. It also allows us to inject scoring logic and run it 46 times faster, per process. A good amount of time was spent to optimize this “virtual world”. Implementing the quaternionic Python module improved the speed 100% over pyquaternion module, which was used at first to handle rotations. We ran the trained agents in real Minecraft and noticed some bugs that had to be fixed, such as clamping the pitch. The architecture of the simulation is based on Unity (a game engine), with a base Entity class that has a transform, start, and update functions. Entities in the simulation are Fireballs, Ghasts, and the Agent itself. The World class represents a singular simulation, and due to this, several simulations can be run in parallel using multiprocessing. It also includes utility functions, such as SphereLineIntersect, which is used for hit detection against fireballs.

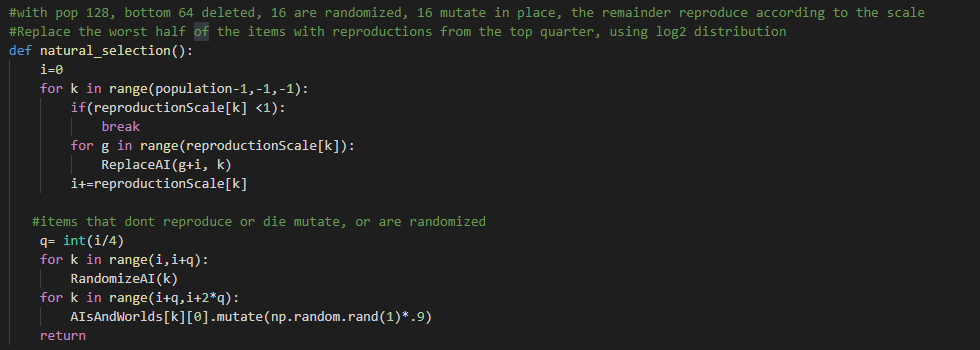

Initially, there were several ideas on how to do selection and scoring: adding a bonus if it was looking close to the ghast and fireball, punishing it for looking straight up or down, small rewards for almost hitting the fireball, doing boom and bust cycles with the population over time, etc.. In the final version, only hitting a fireball and hitting a ghast with a fireball were rewarded, 5 and 50 points respectively, while missing was punished with .125 points. The selection function was a bit more involved. The array is sorted by score, ascending, and the agents “reproduce” according to \(log_2(index) - 1\). For example, in a population of 128 agents, the best ones will reproduce 6 times. The 3rd quartile is 50/50 mutated in place or scrambled, to prevent it from becoming a monoculture.

The biggest hurdles I ran into were overfitting and the lack of randomness no matter what I did from numpy. To start with the latter, even when training didn’t utilize sub processes, scores were more indicative of what AI got lucky ghast spawns either right above or right below them - these AI didnt have results that translated between runs and since luck isn’t heritable, they didn’t learn much either. To remedy that I made a list of spawn points, and the ghasts always start at the first then progress through it as they are killed and respawn. Ultimately this training was still not yielding good results though - agents would slowly spin and look up or down , coincidentally getting the first 3 without really responding to input after a literal year of simulated training time.

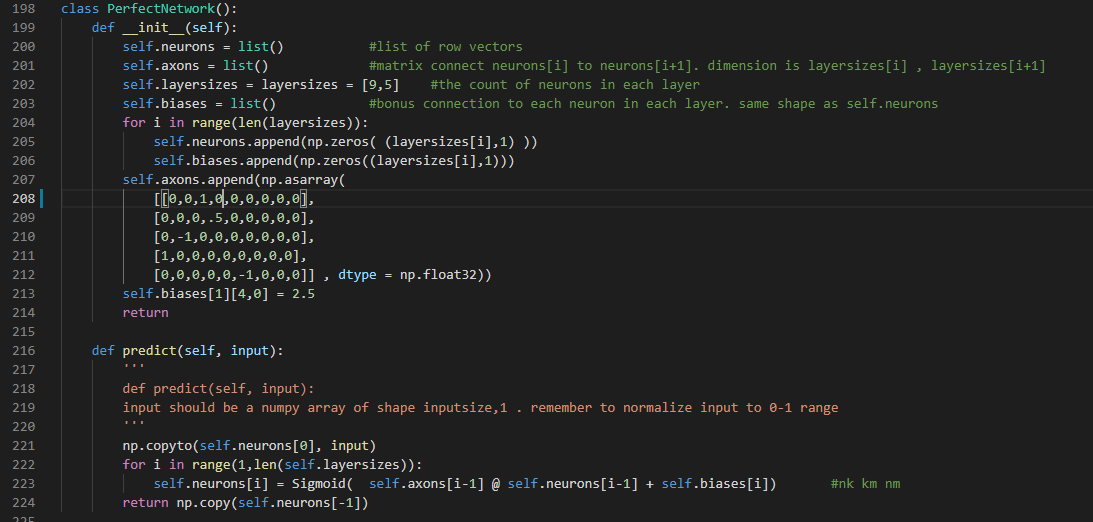

I was about ready to give up on neural networks at this point. I even replaced my selection function with complete randomness to see if I could get anything better by pure luck. I didn’t. I decided to sit down and make one by hand to see what an “ideal” network would look like. I discovered that instead of needing hundreds of neurons and 3-5 layers for what I imagined were complex spatial operations, I really only needed 1 layer of the minimum size, sparsely decorated with 1’s and -1s, with a simple bias to determine when to attack. This was the first agent that actually looked decent.

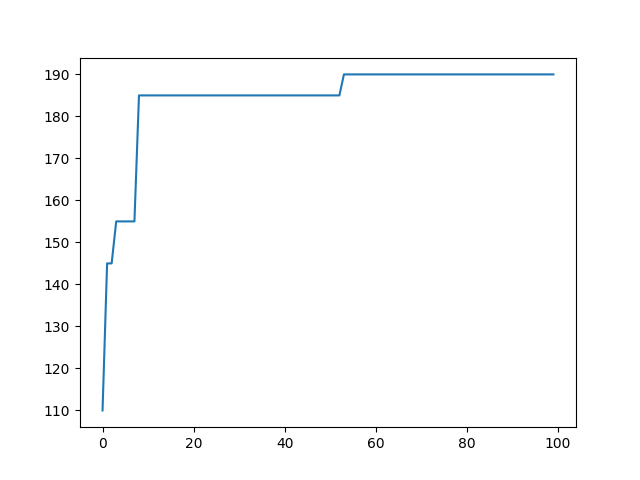

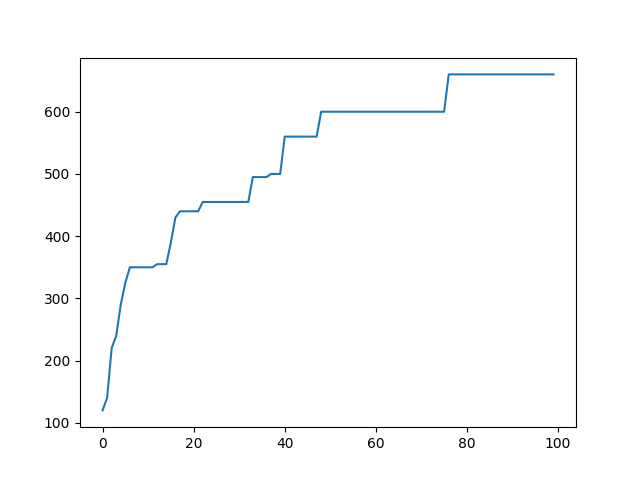

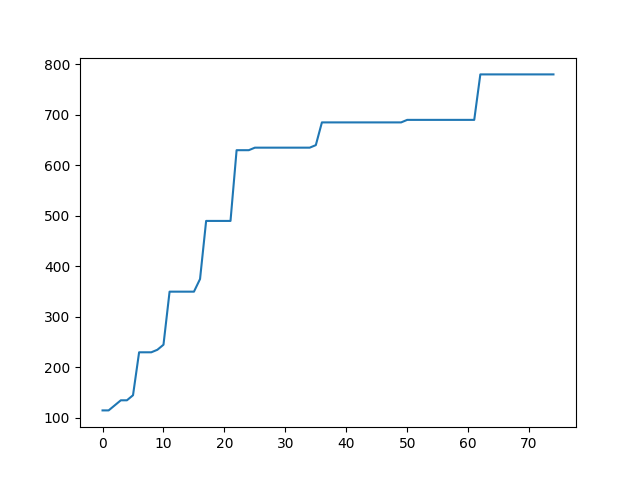

In the final 3 trained agents prior to implementing sexual reproduction, I set the maximum layer size to the input size, and the maximum number of hidden layers to 2. Instead of having values initialized between \(-1/layersize\) and \(1/layersize\), they were expanded to be between -1 and 1. The best bot previous to this scored 190 in the simulation. The best bot after that scored 780, and is the one shown in our video.

Still, there was some weirdness that needed sorting out with how Minecraft and Malmo handle space - their coordinate system is strange, -z seems to be forwards. Also Malmo reports pitch and yaw in a way that doesn’t match their documentation. With some tweaking to how input and output are received and fed between the agent and Malmo, we were able to get good performance out of them. There are problems with the responsiveness but overall it works well for close up ghasts. We scaled outputs linearly to help compensate for the percieved lack of responsiveness.

When I was about to give up on neural networks I considered a few options that were only partially implemented in version 4 of my neural network: making it an ensemble learner and exchanging members via ‘sexual reproduction’ between the agents that reproduced in the evolutionary learner, or making a computation graph that mutated over time. I wasn’t going to finish these ideas, but after submitting I got curious so I went back and gave sexual reproduction a try.

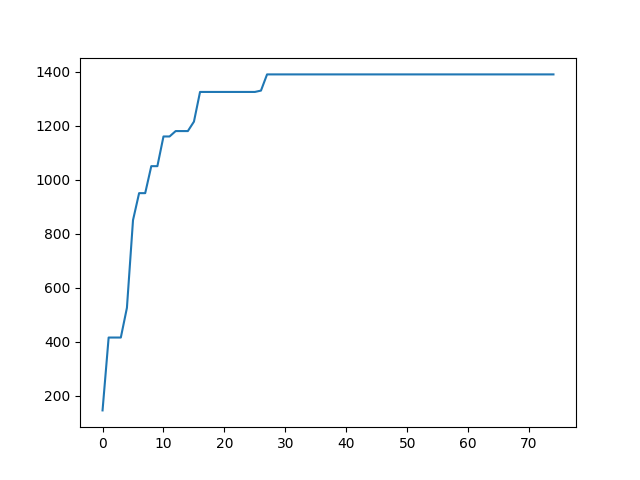

It worked far better than I could have hoped for. Each output of the new ensemble - NeuralNetV4 - is handled by its own network, that has a binary mask it multiplies the input by, meaning each one only takes a fraction of the input. Networks reproduce, with each in the top quartile reproducing twice with two networks ranked worse than it. Each offspring recieves a 50 50 chance of having a given subnetwork from one parent or the other, and either way slightly mutates in place. These ensembles outstrip the previous iterations easily, outtraining them sometimes in as little as 5 generations. These enabled me to make the training more difficult and specific, shrinking the ghasts and moving them further away and making them shoot only if the player is not too close, and punishing the player for attacking with the confidence that it wouldn’t just evolve agents that wouldn’t attack at all.

Evaluation

“Overall I’m more impressed by how well the agents learned in simulation than how well that translated to real Minecraft.” Is what I’d said before going back one last time and discovering a sneaky time.sleep nested in a function call, causing some extra unresponsiveness. With that fixed I’m actually now quite happy with the performance of the bot. I think it does about as well as you could expect any human to, without having actually ever touched minecraft. It was trained entirely in my simulation.

Ultimately I think our bots limitations stem from the precision and timing required for the task, and the imprecision of Malmo - while we should be getting 20 updates per second, it seems obvious from watching it that we’re getting less than that. You can see this in the bot’s wild swinging around as it tries to aim at the ghast - its repeatedly overshooting then overcorrecting until it gets close when it stabilizes, causing it to miss most of the return shots past a certain distance.

Quantitative

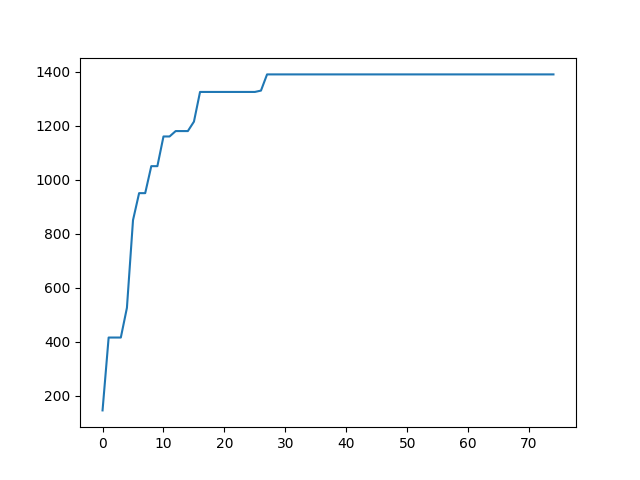

Right: Deeper neural networks, more random initialization (-1 to 1).

|

|

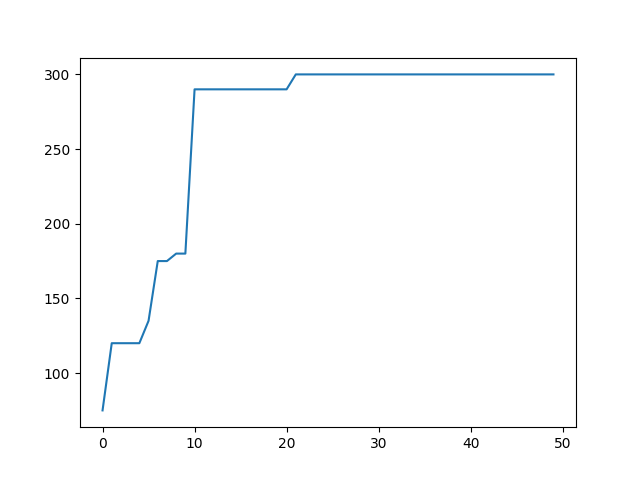

Right: Evaluation time extended from 20s to 40s.

|

|

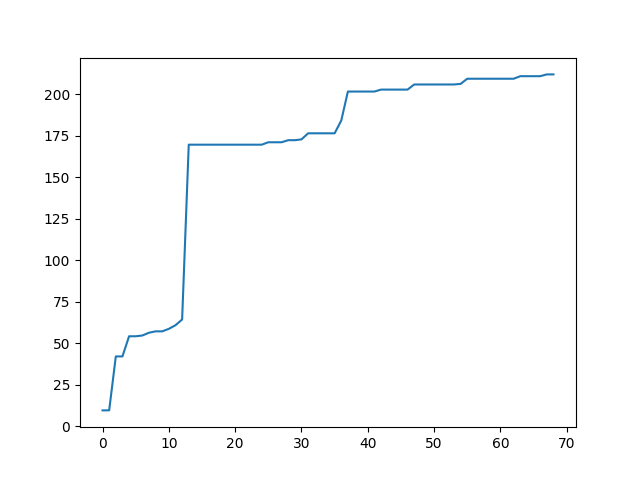

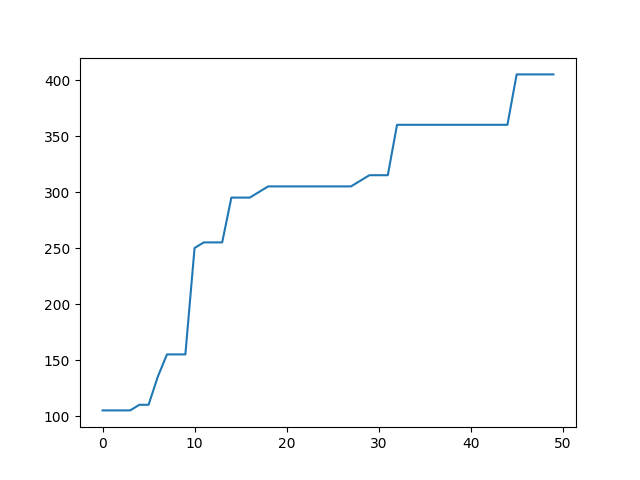

Right: Same thing, but forward is (0, 0, -1), like real Minecraft.

|

|

:—————————————————————————————————————-:

Qualitative

Our simulated Minecraft world showed promising results during training, which initially didn’t translate well. However, in the final version the responsiveness was improved and the agent quality rose high enough to be comparable to a human minecraft player. After training high scoring agents in the simulated Minecraft world, we used the trained agent and fed observations from a real Minecraft world and Malmo.